An initial look on the Kelly Criterion

Level 4 - WAGMI 2.0

Welcome Avatar!

Except for the first section where some background information is provided, this is our first post accessible only by paid subscribers. The aim with it is to dive in deep on the Kelly Criterion, we will discuss what it is, analyze why it is important and explain why the theory underpinning it is vital to understand and become familiar with for an aspiring professional bettor.

Background

In previous substack writings we have introduced and discussed the concept of expected value, often abbreviated EV.

If you feel a need to freshen up your memory on EV, please reread our Betting 101 post.

Among other things, it was mentioned that:

In practice, a great heuristic is to investigate all +EV openings further while always ignoring any -EV bets (possibly taking the other side).

Hence, if you find yourself in a position with a +EV betting opportunity, you should probably execute a trade, one way or another. However, this immediately gives rise to a very interesting question, how much should you bet?

If your goal is to simply maximize the expected value in dollar terms, then the correct strategy is to bet as much as possible, i.e. your full portfolio. It does not require much thinking though to realise that this is an extremely unintelligent approach, within only a couple of bets there is a great chance you will have gone bust already and, in fact, with probability one you will go broke sooner or later if you continue indefinitely. It suffices to say we should be able to do better.

At the other extreme, you do not want to completely waste the opportunity, if there is positive expected value offered, you somehow want to collect at least a bit of it.

This leaves us with an intriguing situation, perhaps best summarized in three main objectives:

+EV opportunity → want to bet more than 0 $.

Uncertain event → cannot risk full portfolio.

Want, for self-explanatory reasons, to introduce some dependence on portfolio size → bet a *fraction* of total bankroll.

The question is, could there possibly exist a *perfect* fraction taking care of our wishes all at once, always answering the “how much should I bet?” question with unparalleled precision?

The Kelly Criterion

The year is 1956. A paper is written. It changes everything. Yet in hindsight, as with any ingenious invention, it seems all so obvious.

John Larry Kelly Jr, a scientist at Bell Labs, takes an attempt at solving the above question, and succeeds.

How?

Let’s dive in!

Instead of considering the betting opportunity as a unique, one-time proposition, Kelly imagined the bettor being offered the same exact bet N times in a row, not perfectly realistic but similar to what is of interest in real life. No single bet determines ones fate, a full sequence does.

Before continuing, we state a couple of necessary definitions below.

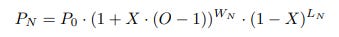

Now, if N is large, then if our strategy is well thought out and we are continously hitting +EV bets, we would somehow expect to have seen some portfolio growth. How do we formulate this reasoning mathematically? We begin by expressing our portfolio after N bets as a function of the other parameters.

This formula makes sense since if a bet wins, and we wager a fraction X of our total portfolio on it, our net increase in portfolio size is X*(ODDS-1), which is to say that our portfolio has been multiplied by a factor of (1 + X(ODDS-1)). Similarly, if the bet is a loss, then we lose the fraction X that we wagered, equivalent to the portfolio being affected by a factor (1-X). Adjusting the presence of each of these two factors with regards to the number of wins/losses, we arrive at the above expression.

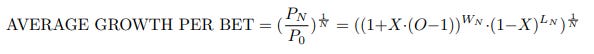

Progressing with a division on both sides of the equality by the value of our initial portfolio, we obtain an equation specifying the total growth over our betting period.

This is interesting, because if we could now find a fraction X that maximizes this growth of our portfolio our problem would be solved. There is a slight complication though, we do still possess quite a lot of dependence on the value of N since the number of wins/losses are more or less derivatives (the financial version of the term) of the number of total bets. Our goal is to find a general solution, not one for every number of iterations.

Since maximizing the total growth over a betting sequence is equivalent to maximizing the average geometric growth provided by each bet, perhaps normalizing the growth could help us forward?

Continuing by distributing the 1/N exponent on the right hand side yields the following, mathematically identical, expression.

At this step this indeed looks very promising, at least for an experienced eye, since as soon as N grows large, the fractions number of wins/number of bets and number of losses/number of bets should *intuitively* move towards the true underlying probabilities. By taking limits and by use of the law of large numbers, average growth turns into expected growth and probabilities (which we are expected to know beforehand) enter the picture.

Voila! We have now managed to transform our abstract idea of finding an optimal bet fraction into an *easily* solvable mathematical problem. Given knowledge of odds and probabilities we are now in a position to instantly compute the exact right fraction that will guarantee to grow our dollars as effectively as possible at every point in time of our betting career.

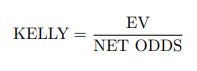

Solving the above optimization problem by way of standard mathematical techniques, we find that the value of X, i.e. the ‘correct’ fraction, from now on simply labeled ‘Kelly’, equals

Autist note: A complete mathematical description and solution of this onedimensional case, together with a shorter discussion, can be found here. The even more interesting multidimensional case will be given a similar treatment in due time.

Digesting the formula

A formula in itself does not reveal much, it simply tells you how to map a specific input to an output. Using such a formula is often a triviality. On the contrary, developing a deep understanding of it may at times require extraordinary measures. As we all know though, any edge always lies in the understanding rather than in the usage. By virtue of this fact the main theme of this brief section is to inspect the obtained formula and analyze its parameters. Fortunately the onedimensional case is pretty straightforward and will therefore offer immediate, actionable advice without adding much complexity.

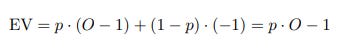

The key to the analysis is to focus on the numerator of the fraction. If you have read our explanation of EV this term is probably recognizable after spending some time staring at it. Indeed, if we were to compute the expected value of the given bet, we would have

which implies that the formula can be rewritten in a simpler form as

a form that instantly reveals two of the most important concepts, the latter for some reason often misunderstood, in determining betting size.

If the expected value increases while the odds stays the same, i.e. the probability goes up, you bet *MORE*.

If two bets offer the same expected value but non-equal odds, you bet *MORE* on the proposition with lower odds.

Autist note: There is a relation between EV and NET ODDS which often complicates things by way of making the underlying concept of ‘holding one of them constant’ to rarely apply. To see the existence of such a relation you could for example try finding a +20 % EV opportunity within an odds range of [1, 1.15].

Is Kelly an exact formula or a mental framework?

Definitely the latter. Four quick notes explaining why:

In real life both odds and probabilities are in constant movement. You do not have the time to play around with calculators and optimize stuff. If there is an opportunity, you simply hit it, and *then* you think. Training yourself afterwards via computing what Kelly would bet to *learn it intuitively* is however much recommended.

Only the onedimensional case has been discussed in this Kelly introduction. In reality you are almost always in the much more advanced multidimensional case, rendering the mission of always betting ‘perfectly’ more or less impossible. If you can handle the math (warning, *ultra-turbos* only) and are interested in the multidimensional case already (will be covered thoroughly in future substack posts), please consider reading the original Kelly paper.

It is much more important to understand what makes Kelly

*increase* or *decrease* its stake, rather than to know the exact number in a specific setting. You want to know *why* and *how* changes in parameters change how you should bet so that you can begin to think in Kelly terms while allocating your precious resources.In theory, basically anything involving money can be modeled using Kelly/geometric mean optimization theory. If you are simultaneously invested in 23 computer coins, 249 stocks and 17 bets the same night you are signing your new insurance contract, you *could* (given payout functions and joint probability distributions) model this exact scenario using the Kelly framework and obtain a result telling you exactly how to distribute your money to achieve optimal growth. Most definitely you would not do it though. However, via familiarity with the *existence* of such an optimal portfolio, you will at all times strive to invest in a way as close to optimum as possible. How will you make sure you move in the right direction? By knowing how every little change to the portfolio affects long term growth. Or in other words, by having Kelly as your best friend.

Any problems on the horizon?

Having read this fairly deep dive on Kelly, we could probably agree on the fact that the beautiful theory behind it is extremely convincing. If theory equaled practice, then it would be all said and done. As Yogi Berra stated though:

In theory there is no difference between theory and practice - in practice there is.

Reviewing the criterion again, now from a more practical but also a more skeptical point of view, a couple of questions regarding the underlying assumptions necessarily arise:

Intrinsic to the Kelly Criterion is the knowledge of true probabilities. With casino games being an exception, possessing this knowledge is in most cases unfortunately impossible. Since Kelly maximizes your long term growth *conditional* on being provided true probabilites, it should not come as a surprise that using *incorrect* input data could severely harm your portfolio returns.

Kelly is what a mathematician would call *asymptotically* optimal, i.e. it is an optimal, outperforming strategy as the number of bets becomes very, very large. Since lots of bettors do not iterate an ‘infinite’ number of times, maybe an analysis of a finite case would suit them better?

If in possession of a large portfolio, getting Kelly size down with your bookmakers/other market participants will be extremely tricky if not impossible. Therefore one could envision a superior strategy that maximizes the probability of reaching these levels/thresholds rather than focusing on impractical “long-term growth”.

In real life bettors do not necessarily care about becoming infinitely richer than their fellow men. Kelly betting is inherently volatile and not for everyone. Two examples:

They may prefer becoming “rich enough” in a non-stressful manner.

They could have a wish of for example never having a larger drawdown than 10 %, a wish that is completely incompatible with Kelly betting.

If we were to comment on these arguments, the large portfolio → cannot get Kelly size down is in our opinion the only compelling one. In future more practical Kelly posts we will make sure to give this case a profound analysis and also explain why we believe that the rest of them are of no interest for a true BILL BETTOR. And, it is important to mention it yet again, the output from the formulas is *not* all there is to it, truth lies not in the numbers but in understanding the effects the various parameters have on them.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that it may not always, under every circumstance, be optimal in practice, Kelly knowledge is in our opinion one of the most indispensable frameworks the betting world has to offer, challenged only by a few Bayesian (Bayes, another genius soon to be introduced to the Jungle) concepts. The moment you get used to observing everything from a Kelly/growth/geometric mean maximization point of view, things that have puzzled you before immediately begin to make complete sense. You get the feeling of “ah, it had to be” again and again. And while reality may restrict the Kelly bettor from performing *infinitely* better than everyone else, we are very confident that when push comes to shove, the difference between the guy learning ‘the Kelly way’ thoroughly versus the one ignoring/missing it will be *massive*. Not only bankroll-wise.

Until next time…